Benefits of Hill Sprints for Beginner Runners

For those relatively new to regular running, the notion of introducing maximal effort hill sprints is often met with concern over the possibility of overtraining and encouraging injury.

And yet, including one or two weekly hill sprint sessions into your training may well be safer than just knocking out long distances on flat ground.

The strength training stimulus that hill sprints provide is thought to play a major role in reducing susceptibility to injury. What’s for sure is hill sprints increase the power and efficiency of your stride, enabling you to cover more ground with each stride using less energy. Still worried about hill sprints? Read on…

Hill sprints for neuromuscular fitness

In the article Components Of A Training Plan, we looked at the importance of including different types of runs to your training in order to improve pace. We noted that running fitness has three components which although inter-related are stimulated by different types of training: aerobic fitness, neuromuscular fitness, and specific endurance.

Hill sprints are an example of a type of training that enhances neuromuscular fitness. In other words communication between the brain and the muscles. Working at maximal or near-maximal levels challenges the nervous system to activate huge numbers of motor units and fire them quick enough to generate high force whilst resisting fatigue.

Stride frequency, stride length and resistance to fatigue all depend on the efficiency of communication between the brain and muscles and are all vital for production of optimum power, efficiency, and resistance to fatigue. Though long runs are important for developing aerobic fitness, without sufficient neuromuscular fitness form can deteriorate, inefficiency, and fatigue set in, all of which are often associated with injury.

Hill sprints allow you to push your body and generate high leg turnover (cadence) without actually running that fast. This is of great significance as maximum speed work on flat ground is often associated with injury such as hamstring strains. Running uphill is also thought to stimulate form improvement by imposing demands that flat running does not.

For example, though lifting the knee high is not something you should consciously attempt during your flat runs, being forced to do it by a hill could well help pave the way for the natural, unconscious development in knee raise that you will experience as your strides become more powerful. Likewise, hill sprints demand a lifting of the toe (ankle dorsiflexion) prior to landing, something that again is associated with power generation and increase in stride length.

In case “maximal or near-maximal levels” has struck fear into anyone’s hearts, we are only talking about duration of approximately 8-12 seconds. Your introduction to hill sprints may be just a couple of these with a 2-3 minute rest in between. But how steep a hill do we need?

Hill gradients

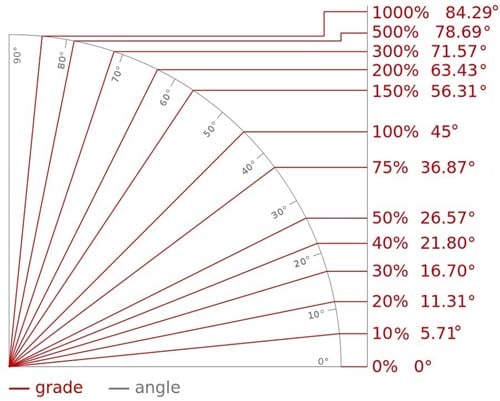

The gradient of a hill is the vertical distance (climb) expressed as a percentage of the horizontal distance traveled. A 100% gradient is therefore where the climb is equal to the horizontal distance traveled, also known as a 1:1 slope. A 10% gradient (1:10) on the other hand has a climb equal to 10% of the horizontal distance traveled. Grade should not be confused with angle. As we can see in the diagram below, a 100% grade is only a 45o angle.

Grades and Degrees (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Guinness Book of World Records lists the world’s steepest road as Baldwin Street in Dunedin, New Zealand, with a gradient of 38% (1 in 2.86) at its steepest section. Needless to say, where there is a challenge there is a race, and indeed every September thousands of people turn up to take part in The Baldwin Street “Gutbuster,” 400 metres including ascent and descent, the current record of 1 minute 56 seconds set in 1994.

Baldwin Street: The World’s Steepest Road (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

As we can see in the photos above, 38% is pretty hardcore. Generally speaking, hill sprints use gradients between 6% (1:16.5) and 25% (1:4). Treadmills can be useful in discovering what a gradient like that feels like but these days most GPS watches conveniently give gradient information.

Incorporating hill sprints into your week

- For novice runners, the first session of hill sprints should be just one or two 8-second sprints on a 6 to 8% gradient.

- Recovery time needs to be sufficient to allow the same distance to be achieved in each sprint. This will vary according to the runner; it may be the time it takes to walk back down the hill, maybe 2-3 minutes – whatever it takes in order to allow maximal effort for each sprint.

- It is also vital not to jump too soon into several sets as the explosive maximal effort employed during those 8 seconds places a great amount of stress on the muscles, tendons and ligaments.

- Also, it is very important that hill sprints be preceded by a suitable dynamic warm up such as the Lunge Matrix followed by a 1 to 2 mile easy pace warm up on flat ground. A cool down run at easy pace is also advised.

- Two sessions a week will be sufficient and gains are normally rapid. The number of sprints performed in each session can typically be increased by 1 or 2 every week. Once you are doing 10 sprints each session (twice a week), you could increase the duration of the sprints to 10 seconds.

Again, on paper this may seem little but the increase in demand will be considerate. A month or so after this, choose a hill or section of the hill with a greater gradient, say 10%. A month later, progress to 12 second sprints, etc.

Here is a cool video of James Carney (13:30 5k runner) performing explosive hill sprints in Boulder, Co.

Hill sprints can increase stride power, build leg strength and increase running efficiency, all of which potentially decrease susceptibility to injury. Have a go, just remember to follow the gradual progression outlined above and take it slow.

post by https://runnersconnect.net/